Not long ago, I saw a patient in my clinic who had previously undergone radiotherapy for Dupuytren’s disease. She returned, worried that her condition had “progressed.” On examination, however, her problem was not progression of Dupuytren’s contracture at all. Instead, she had developed a trigger fingers. I referred her to a surgeon to consider a corticosteroid injection. But that clinical encounter left me with a question: Are Dupuytren’s contracture and trigger finger connected?Dr Richard Shaffer The answer is not straightforward. These two hand conditions are traditionally described as separate entities, but they often occur in the same age group, share risk factors, and may even interact biologically. Recent research has shed more light on whether the link is real. Understanding Dupuytren’s Contracture Dupuytren’s contracture is a chronic disorder of the palmar fascia. Over time, abnormal production of collagen (especially type III collagen) leads to nodules and cords in the palm and fingers. These cords shorten, drawing the fingers into flexion contractures that limit hand function. Prevalence: Around 3–6% of Caucasians worldwide. In some northern European populations, the prevalence is much higher, with up to 50% of men over 75 affected. Risk factors: Age, male sex, northern European ancestry, diabetes, epilepsy, smoking, alcohol use, HIV infection, manual labour, and associated conditions such as Ledderhose and Peyronie’s disease. Impact: The condition can progress slowly but severely, leading to loss of function. Treatments include collagenase injections, needle aponeurotomy, and fasciectomy, while radiotherapy may play a role in early disease to prevent progression. Histologically, …

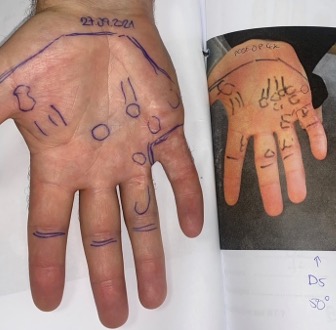

Not long ago, I saw a patient in my clinic who had previously undergone radiotherapy for Dupuytren’s disease. She returned, worried that her condition had “progressed.” On examination, however, her problem was not progression of Dupuytren’s contracture at all. Instead, she had developed a trigger fingers.

I referred her to a surgeon to consider a corticosteroid injection. But that clinical encounter left me with a question:

Are Dupuytren’s contracture and trigger finger connected?

The answer is not straightforward. These two hand conditions are traditionally described as separate entities, but they often occur in the same age group, share risk factors, and may even interact biologically. Recent research has shed more light on whether the link is real.

Understanding Dupuytren’s Contracture

Dupuytren’s contracture is a chronic disorder of the palmar fascia. Over time, abnormal production of collagen (especially type III collagen) leads to nodules and cords in the palm and fingers. These cords shorten, drawing the fingers into flexion contractures that limit hand function.

- Prevalence: Around 3–6% of Caucasians worldwide. In some northern European populations, the prevalence is much higher, with up to 50% of men over 75 affected.

- Risk factors: Age, male sex, northern European ancestry, diabetes, epilepsy, smoking, alcohol use, HIV infection, manual labour, and associated conditions such as Ledderhose and Peyronie’s disease.

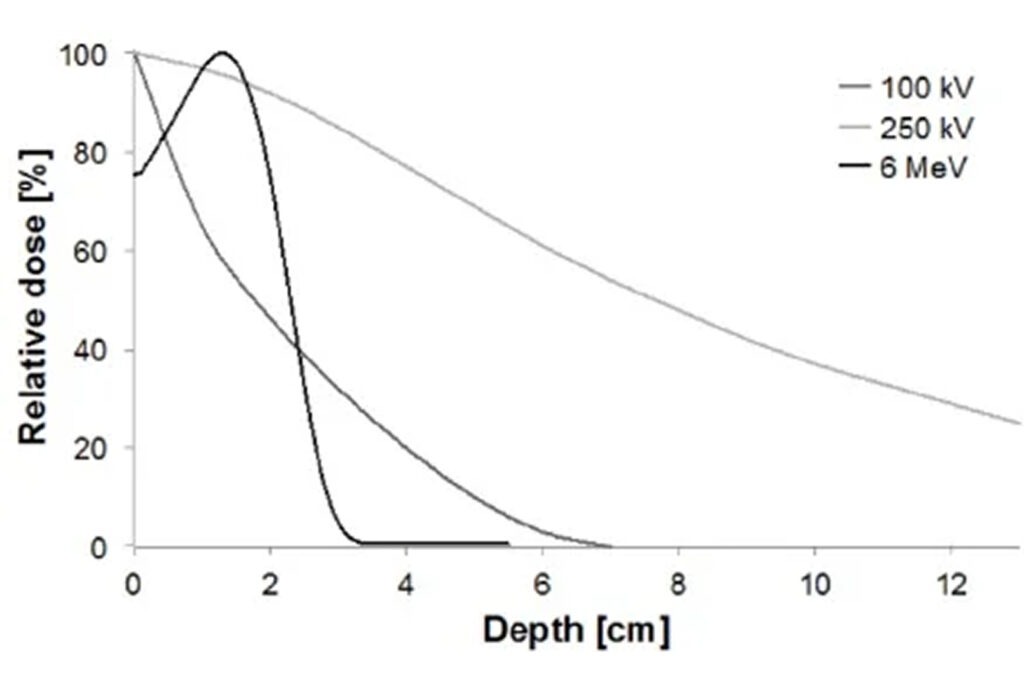

- Impact: The condition can progress slowly but severely, leading to loss of function. Treatments include collagenase injections, needle aponeurotomy, and fasciectomy, while radiotherapy may play a role in early disease to prevent progression.

Histologically, Dupuytren’s is considered a fibroproliferative disorder. Myofibroblasts and excess collagen deposition drive the process, much like pathological scarring.

Understanding Trigger Finger

Trigger finger, or stenosing tenosynovitis, is different. It occurs when the flexor tendon cannot glide smoothly through the A1 pulley, typically because the pulley has thickened and narrowed. Patients describe painful clicking, catching, or even the finger “locking” in flexion.

- Prevalence: Around 2% of the general population. It is more common in women, particularly in their 50s and 60s.

- Risk factors: Age, female sex, diabetes, hypothyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, carpal tunnel syndrome, and occupations requiring repetitive gripping or manual tasks.

- Treatment: Corticosteroid injections, splinting, and surgical release of the A1 pulley.

Pathology: Trigger finger is not a primary fibroproliferative disease. Instead, the pathology reflects inflammation and degenerative change in the tendon sheath:

- The A1 pulley can become up to three times thicker than normal.

- Fibrocartilaginous metaplasia often develops in the pulley due to chronic friction.

- The flexor tendon itself may show nodularity and degenerative change.

So while there is thickening and fibrocartilaginous change, these are secondary to inflammation and mechanical stress, unlike Dupuytren’s where the fibroproliferative process is primary.

Why Consider a Connection?

At first glance, these conditions affect different structures:

- Dupuytren’s = palmar fascia.

- Trigger finger = tendon sheath and A1 pulley.

Yet they often occur in the same patients. Several hypotheses might explain the overlap:

- Shared risk factors. Both are more common with advancing age, in people with diabetes, and in those engaged in repetitive manual work.

- Mechanical interaction. Dupuytren’s nodules or cords – especially when they involve the vertical septa – may physically impinge on the flexor tendon sheath, causing triggering.

- Inflammatory cross-talk. Inflammation from trigger finger may accelerate fibrosis in predisposed fascia, hastening the onset of Dupuytren’s.

- Genetic predisposition. Patients prone to fibroproliferative disorders may have overlapping pathways that increase susceptibility to both.

- Diagnostic confusion. Inflammatory nodules from trigger finger can sometimes mimic early Dupuytren’s, leading to mislabeling.

These possibilities raise an important question: is the coexistence of the two conditions simply coincidence, or is there a genuine biological link?

Evidence From Yang et al. (2019)

A key study examining this issue was published by Yang and colleagues in 2019.

Study design

- Retrospective review of 238 patients seen by a hand surgeon between 2014 and 2017.

- Patients had either Dupuytren’s contracture, trigger finger, or both, in the same hand.

- Demographics, comorbidities, and clinical data were analysed.

Findings

- 192 patients had trigger finger.

- 89 patients had Dupuytren’s.

- 43 patients (18%) had both conditions in the same or adjacent digits.

Statistical analysis

- Univariate analysis:

- Trigger finger, age, and sex were significantly associated with Dupuytren’s.

- Dupuytren’s and sex were significantly associated with trigger finger.

- Diabetes, manual labour, smoking, and alcohol were not significant.

- Multivariate analysis:

- Age remained significant for Dupuytren’s.

- The presence of trigger finger was strongly associated with Dupuytren’s, with an odds ratio of more than 300.

Conclusion

The study found a significant association between the two conditions, independent of most shared risk factors. Patients with trigger finger appear to be at increased risk of having or developing Dupuytren’s disease, and vice versa.

Possible Mechanisms in Light Of The Evidence

Yang et al. and earlier researchers suggest several mechanisms that may explain this strong association:

- Mechanical impingement: Dupuytren’s cords involving the vertical septa may compress tendons and the pulley system, creating or worsening triggering.

- Inflammatory acceleration: The inflammation of trigger finger may induce fibrotic activity in adjacent palmar fascia, accelerating Dupuytren’s in predisposed individuals.

- Post-surgical effects: After A1 pulley release, local healing and inflammation may act as a fibrotic trigger, unmasking latent Dupuytren’s.

- Subclinical coexistence: Patients may have early Dupuytren’s that is not obvious until trigger finger prompts closer examination.

Clinical Implications

For clinicians, these findings are highly relevant:

- Examine for both. When a patient presents with trigger finger, carefully check for Dupuytren’s nodules or cords. Similarly, screen Dupuytren’s patients for triggering.

- Patient education. Explain that the two conditions are associated. Developing one raises the likelihood of developing the other.

- Treatment planning.

- If both are present, a simple A1 pulley release may not be enough. In selected patients, a combined procedure (A1 pulley release plus limited fasciectomy) may be appropriate.

- Postoperative inflammation can be a double-edged sword – relieving one problem but accelerating fibrosis in the fascia.

- Radiotherapy perspective. Radiotherapy is used in early Dupuytren’s but not in trigger finger. Still, awareness of this association helps radiation oncologists understand why some patients present with “progression” that is actually triggering, not true Dupuytren’s.

Conclusion

So, are Dupuytren’s contracture and trigger finger connected?

The answer appears to be yes. They share risk factors, they frequently occur together, and their interaction may be more than coincidence. While trigger finger is an inflammatory and mechanical condition with secondary fibrocartilaginous changes, and Dupuytren’s is a primary fibroproliferative disease, the two can influence each other.

For clinicians, this means vigilance: always look for both, educate patients about the overlap, and plan treatment accordingly. For patients, it means that developing one condition should prompt awareness of the other.

And for those of us who treat Dupuytren’s with radiotherapy, it’s a reminder that even when we succeed in halting fibrotic progression, other conditions like trigger finger can still affect hand function and quality of life.

✅ Reference: Yang K, Gehring M, Bou Zein Eddine S, Hettinger P. Association between Stenosing Tenosynovitis and Dupuytren’s Contracture in the Hand. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019;7:e2088.