Two Climbers, Same Diagnosis This week in clinic, I met two climbers. One was in his 20s. The other was in his 30s. Both had been diagnosed with Dupuytren’s disease. And both were worried about what this might mean for their climbing. For people who climb, the idea that Dupuytren’s could affect their grip or flexibility is unsettling. Even the thought that climbing might be threatened can feel overwhelming. Climbing isn’t just a hobby—it’s central to identity, fitness, and community. That’s why understanding Dupuytren’s disease in climbers is so important. What is Dupuytren's disease? Dupuytren’s disease (sometimes called Dupuytren’s contracture) is a condition where the connective tissue in the palm—the palmar fascia—gradually thickens and tightens. It usually starts with small lumps (nodules) in the palm. These can develop into cords under the skin. Over time, the cords may pull one or more fingers into a bent position. The ring and little fingers are most often affected. The condition is usually painless, but as fingers begin to bend, daily activities—like climbing, typing, or shaking hands—can be affected. Why are climbers at higher risk? We know climbing is a risk factor for Dupuytren’s, but the mechanism is different from the usual trauma risks. Most hand trauma is either: Sharp trauma – fractures, cuts, or surgery. Blunt trauma – impact, vibration, or heavy repetitive force. Climbing is unique. Climbers repeatedly support much of their body weight through small holds, forcing the fascia, tendons, and pulleys in the hand to absorb tremendous loads. Over …

Two Climbers, Same Diagnosis

This week in clinic, I met two climbers. One was in his 20s. The other was in his 30s.

Both had been diagnosed with Dupuytren’s disease. And both were worried about what this might mean for their climbing.

For people who climb, the idea that Dupuytren’s could affect their grip or flexibility is unsettling. Even the thought that climbing might be threatened can feel overwhelming. Climbing isn’t just a hobby—it’s central to identity, fitness, and community.

That’s why understanding Dupuytren’s disease in climbers is so important.

What is Dupuytren's disease?

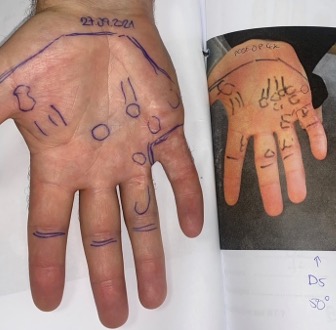

Dupuytren’s disease (sometimes called Dupuytren’s contracture) is a condition where the connective tissue in the palm—the palmar fascia—gradually thickens and tightens.

- It usually starts with small lumps (nodules) in the palm.

- These can develop into cords under the skin.

- Over time, the cords may pull one or more fingers into a bent position.

The ring and little fingers are most often affected. The condition is usually painless, but as fingers begin to bend, daily activities—like climbing, typing, or shaking hands—can be affected.

Why are climbers at higher risk?

We know climbing is a risk factor for Dupuytren’s, but the mechanism is different from the usual trauma risks.

Most hand trauma is either:

- Sharp trauma – fractures, cuts, or surgery.

- Blunt trauma – impact, vibration, or heavy repetitive force.

Climbing is unique. Climbers repeatedly support much of their body weight through small holds, forcing the fascia, tendons, and pulleys in the hand to absorb tremendous loads.

Over time, this repeated strain appears to trigger changes in the fascia that can lead to Dupuytren’s.

Research on Dupuytren's disease in Climbers

One of the most influential studies came from the Climbers’ Club of Great Britain.

- Questionnaires were sent to all 1,100 members.

- Over 500 responded (an excellent response rate).

- The average age was 54, and nearly all were men.

The findings were striking:

- Prevalence: Almost 20% of male climbers had Dupuytren’s disease—much higher than the general population.

- Intensity matters: Climbers with Dupuytren’s had higher “lifetime climbing intensity scores.” The more they climbed, and the harder they climbed, the greater the risk.

- Earlier onset: Climbers developed Dupuytren’s at a younger age compared with non-climbers.

- Greater severity: Climbers had more finger contractures than expected.

Other risk factors—such as smoking, alcohol, epilepsy, manual work, and previous injuries—did not explain the difference. Family history did make a difference: climbers with a family history were more likely to develop Dupuytren’s.

But here’s the key point:

Even if you don’t have a family history, climbing itself can bring Dupuytren’s on earlier and make it more severe.

Do Climbers With Dupuytren's Have to Stop Climbing?

The main takeaway is not that climbing has to stop, but that climbers should be aware of the risks and know what signs to look for. It’s not about being told what you can and can’t do, but you do need to arm yourself with the best information possible to take your own decisions.

Some climbers continue climbing with little difficulty for many years. Others adapt their style, take breaks during treatment, or use supportive strategies. The most important thing is to recognise changes early and explore treatment options at the right stage.

Treatment Options For Dupuytren's Disease

Treatment depends on how advanced the condition is. Broadly, Dupuytren’s disease falls into two categories:

- Early or mild Dupuytren’s (nodules or cords, but no contracture or only mild bending up to 20°)

- Observation: Regular monitoring is important, especially if the disease is stable.

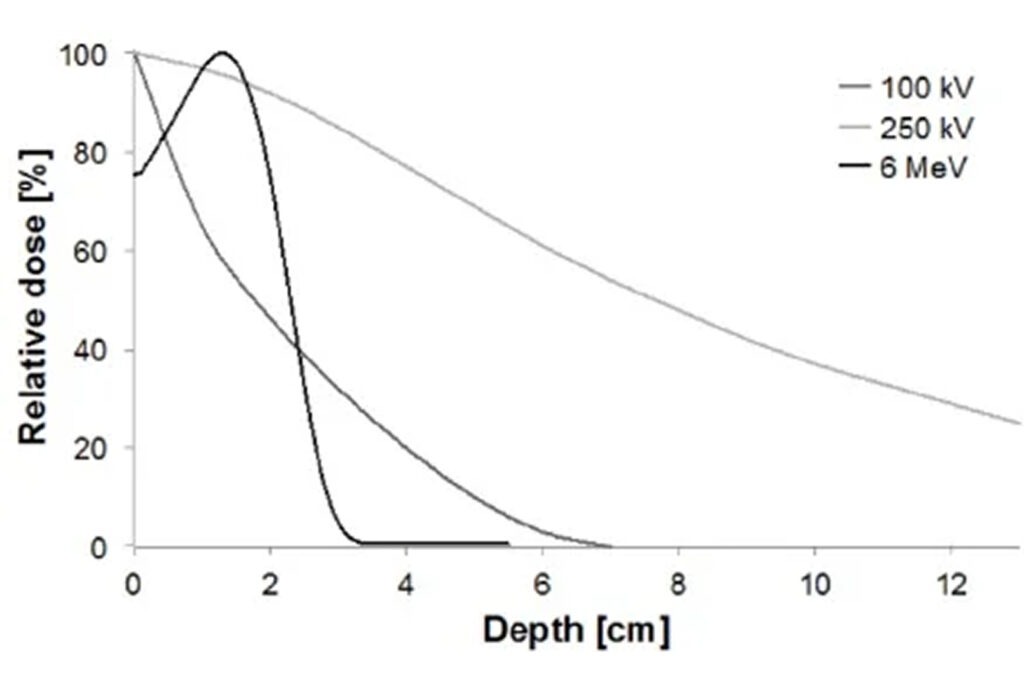

- Radiotherapy: A standard treatment for early Dupuytren’s. Low-dose radiotherapy affects the biology of the disease, slowing or stopping progression and helping prevent contractures from developing. It is especially valuable for younger patients or those at high risk of progression.

- Advanced Dupuytren’s (contracture of 30° or more, where fingers are mechanically bent)

- Needle aponeurotomy: A minimally invasive technique to release cords with a fine needle.

- Collagenase injections: Enzymes soften the cords so they can be broken.

- Surgery: Reserved for more severe cases, where larger amounts of tissue need to be removed.

The principle is simple:

- Early Dupuytren’s is a biological problem → best treated with radiotherapy to prevent progression.

- Advanced Dupuytren’s is a mechanical problem → best treated with procedures that release or remove cords.

This way of thinking helps guide patients to the right treatment at the right time.

Can Dupuytren's Disease Be Prevented If You Climb?

At the moment, there is no proven way to prevent Dupuytren’s. But climbers can take some practical steps:

- Rest and recovery: Allow hands adequate time to recover from heavy climbing sessions.

- Early diagnosis: Catching Dupuytren’s when there are nodules or cords, but before fixed contractures develop, gives more options for treatment.

- Awareness of symptoms: Know what to look for—lumps, cords, or changes in finger flexibility.

If you notice changes, don’t wait until fingers are bent. Early intervention makes a big difference.

Living With Dupuytren's As A Climber

Having Dupuytren’s doesn’t mean the end of your climbing journey. Many climbers adapt and continue the sport they love.

- Some modify grip styles or training volume.

- Others combine treatment with careful hand management.

- A structured observation program can help track progression and guide timing of treatment decisions

The key is to work with a specialist who understands the biology of the disease and can give advice as to how to treat the disease early to prevent contracture and the need for surgery.

What i Tell My Patients

Here’s what I share with climbers in clinic:

- Dupuytren’s is more common in climbers than in the general population.

- It may appear earlier and progress more aggressively.

- Family history increases risk but climbing itself is a risk factor, even without family history.

- Early treatment with radiotherapy exists and is highly effective at preventing progression.

- If radiotherapy isn’t yet appropriate, a structured observation program is the best way to monitor and act at the right time. [Read more about structured observation here.]

Final Thoughts

Climbing is an extraordinary sport, and having Dupuytren’s disease doesn’t mean you have to give it up.

What matters most is recognising the signs early and understanding your treatment options. Radiotherapy in the early stages and surgical treatments for advanced disease provide a clear pathway for managing Dupuytren’s effectively.

If you’re a climber and you’ve noticed changes in your hands – lumps, cords, or fingers that don’t quite straighten – don’t ignore them. The sooner you seek advice, the more options you’ll have.

If you’re a climber living with Dupuytren’s and want to know more about treatment options – including radiotherapy – feel free to reach out. You don’t have to face this condition alone, and early action can make all the difference.

Logan AJ, Mason G, Dias J, et al Can rock climbing lead to Dupuytren’s disease? British Journal of Sports Medicine 2005;39:639-644.